Indigenous Law Research Unit at UVic takes a relationship-first approach to working with Indigenous nations to revitalize their laws

In 2019, the Government of British Columbia passed the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act (“Declaration Act”). Strengthening Indigenous legal orders is essential to fulfilling the Declaration Act. That’s why the Foundation granted $1.2 million in operational funding to the Indigenous Law Research Unit (ILRU). This grant will be paid out over three years, allowing ILRU to build strong relationships with the Indigenous communities they work with to revitalize their legal orders.

Indigenous legal orders: what are they?

In the new Professional Legal Training Course practice materials, prepared by ILRU, Indigenous laws are described as the system of “reasoned principles and processes that Indigenous societies used and still use to govern themselves.” Indigenous societies have always had legal orders and systems and each Indigenous society has its own set of legal orders. For example, Haisla law, Secwépemc law, and WSÁNEĆ law deal with matters differently. While these legal orders never stopped evolving alongside the Canadian legal system, they have existed for many generations in the context of a colonial legal system that sought to extinguish Indigenous legal orders.

“Indigenous law hasn’t been left intact as a result of recent history,” says Val Napoleon, the founding director of ILRU, referring to how colonization stripped Indigenous peoples of their rights to practice their law and customs. She is a research chair holding the title of Law Foundation Chair of Indigenous Justice and Governance at the University of Victoria’s Faculty of Law.

Reinvigorating Indigenous laws

ILRU has helped Indigenous communities revitalize governance and decision-making protocols related to the rights and welfare of children, governance structures and citizenship, and collaborative agreements for managing shared resources like water.

Together, ILRU and the communities it works with identify key areas of governance and the substantive and procedural values that the community wants to uphold through the law. Then, they identify decision-makers and map out people’s obligations to each other and to a legal tradition. They also consider possible consequences when a law is breached. This is all part of the process to articulate, re-state, and reform Indigenous laws so that they can be applied to today’s challenges and realities.

Focusing on relationships with Indigenous communities

Napoleon emphasizes that there’s no right way to set about understanding, articulating, and reinvigorating Indigenous laws. It’s a journey that can take years. ILRU devotes almost as much time to laying the groundwork of strong relationships as it does to legal research. That relationship-building work often includes hosting conversations that get people thinking about what law means to them and understanding the history of Indigenous law.

Indigenous legal orders and legal traditions do not map directly onto Canadian legal systems, which are rooted in the centralized authority of a state government and rely on written statutes and court precedents.

In contrast, Indigenous laws are often recorded and passed down through stories, songs, dances, art, and ceremonies. This might also happen in texts and practices that are not always recognized as legal resources in Canadian law. Indigenous law also tends to focus on relationships and what people owe to each other as family — in societies where definitions of the family might extend to the entire community. “What we’re creating space for is Indigenous peoples to articulate the law of their own non-state, decentralized societies. From this place of strength, Indigenous law can speak to Canadian law and negotiate its terms,” explains Napoleon.

Operational funding makes ILRU’s work possible

ILRU focuses on building relationships with people to ensure successful projects. While legal scholars draft project outputs, participants are invited to revise their contributions before the research is finalized. This practice is meant to restore people’s power and agency over their words. The emphasis on building relationships is why the Foundation felt it was crucial to offer operational, multi-year funding.

“Funding individual projects on a time-limited basis results in a precarious situation that makes this type of long-term work really difficult,” says Leah Combs, Program Director for Indigenous Justice at the Foundation. “Multi-year operating funding will help ILRU to invest in building ongoing relationships with the communities that they engage with.”

With stable funding in place, ILRU continues to work towards a future where, as Napoleon has written, a resurgence of Indigenous law “will make a symmetrical relationship possible with Canadian law — leaving behind the colonial asymmetry which denied and disregarded Indigenous legal traditions.”

Learn more about Indigenous Law Research Unit’s on its website: ilru.ca

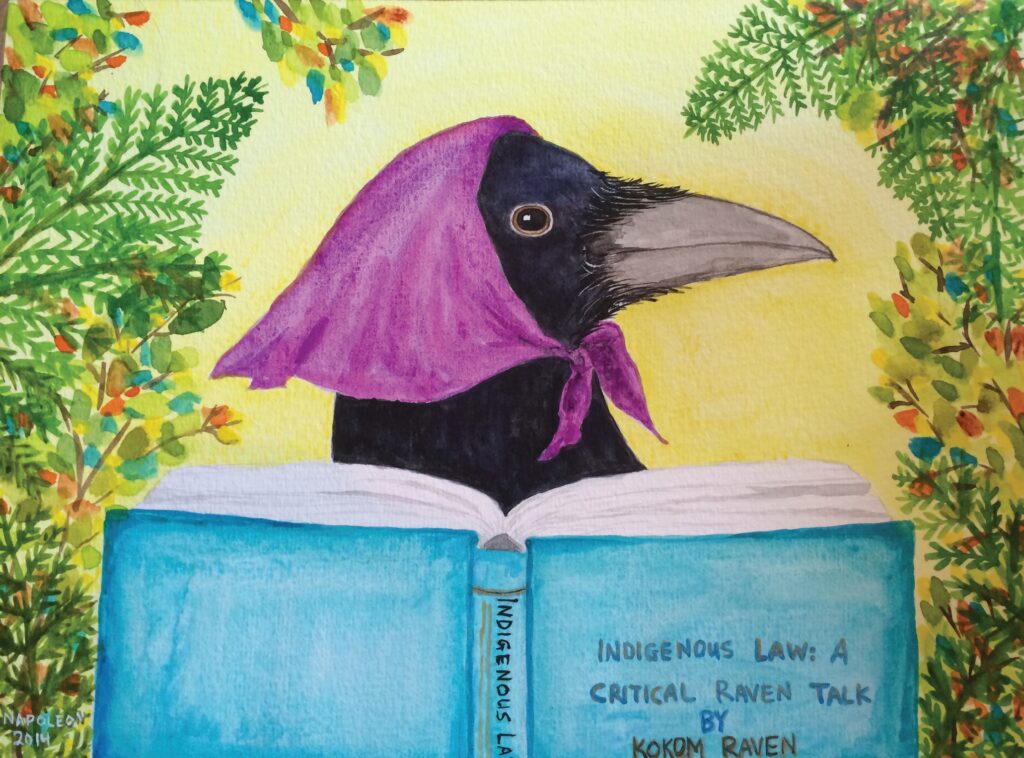

“TEACHER” BY VAL NAPOLEON

USED WITH PERMISSION OF THE ARTIST

PHOTO: IAN CRAWFORD